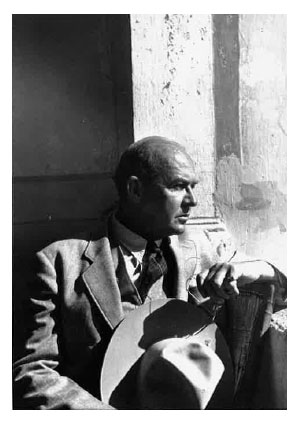

About Witter Bynner (1881-1968)

a versatile man of letters

In the more than eight decades of his life, Witter Bynner was a tireless member of a rare species in our cultural scene, that of the versatile man of letters, whose whole working career was given to the act of literature, with all its involvements not only in many forms of literary statement, but also in Platonian responses to the civil values of free existence. He was an eloquent orator, in poetic forms, who spoke out for the individual dignity of his fellow men, whether in terms of politics, popular mores, or artistic commitment.

graduated from Havard summa cum laude

His long career began during his undergraduate days at Harvard, where he was graduated summa cum laude in 1902. He was the Phi Beta Kappa poet in 1907 with Young Harvard, which became his first book. It was followed by a long list of works, extending until 1960, when Alfred Knopf, the publisher of all but a few of his copious bibliography, brought out his last, and in many ways, his most remarkable work entitled New Poems, 1960.

Other people die, why can't I?

His literary acquaintanceship went back as far as George Meredith, to whom he made a youthful pilgrimage, and included such other figures as Mark Twain and Henry James, continuing through the decades to reach out to the young writers of the mid-sixties, when he suffered the series of emotional and physical disasters which rendered him inactive and, in effect, unreachable, until his merciful deliverance by a blessedly placid death on June 1, 1968, at the age of 87. His last words, suddenly articulated despite his paralyzed state, were said to be, "Other people die, why can't I?"

"I fear I must be the Witter of your discontent."

A man of commanding stature, splendid good looks, and infectious energy, he presided throughout five decades, by common consent, over the cultural and convivial life in Santa Fe. His wit was a delight. It ranged through every degree of style, not disdaining ribaldry and brilliant puns, and it often took your breath away with its instant response to an unexpected lead. One early example of the latter: on his first youthful lecture tour he was introduced by a local worthy to a provincial "lyceum" audience as the "eminent American writer, Mr. William Winter." Already rigid with stage fright, Bynner was further appalled by this, but then, joyfully inspired, rose to his feet and said, "Ladies and gentlemen, I fear I must be the Witter of your discontent."

his generous and time-giving encouragement of younger poets was legendary

Anyone who spent an intimate evening in Santa Fe in the fine library of he and his partner of 30 years, poet Robert Hunt, with a handful of like-minded men and women of wide culture and high wits, will keenly remember his presence, his gusty humor, his generous sensibility in honor of any honest human manifestation, his range of civilized and often hilarious reference, and above all his feeling for the common cause of human life itself, with all his hopes, wonders, and satisfactions, which he saw as deserving of tolerance and respect even at its most pathetic or misguided. Beyond all this, his generous and time-giving encouragement of younger poets was legendary.

a poet of deceptively simplistic technique

Witter Bynner's own art as a poet of deceptively simplistic technique, embodying forth a unique lyric vision, belongs safely to the future. He was allied to a great tradition of letters entirely beyond the fashions of his time, a tradition rooted in those verities of literary art which always survive the fugitive urgencies of any passing hour.

Courtesy of the American Academy of Arts and Letters